From Doing Sustainability to Being Sustainable – A Guide for Business Leaders

John Barcroft

Founder & Sustainability Consultant

The Environmental Edge

In 2025, the sustainability bubble burst, or was at least significantly deflated. Regulatory and political shifts in Brussels and Washington slowed momentum: the EU’s CSRD accelerant was heavily diluted and the froth of the sustainability market was blown away by pushback from vested interests and a political swing to the right.

Yet in this pause lies an opportunity, a silver lining. Business leaders can rethink, reset and refocus how they approach sustainability - moving from incremental, compliance driven efforts to genuinely sustainable business models. Before exploring how, it’s worth understanding where sustainability thinking stands today.

Evolving Views of Sustainability

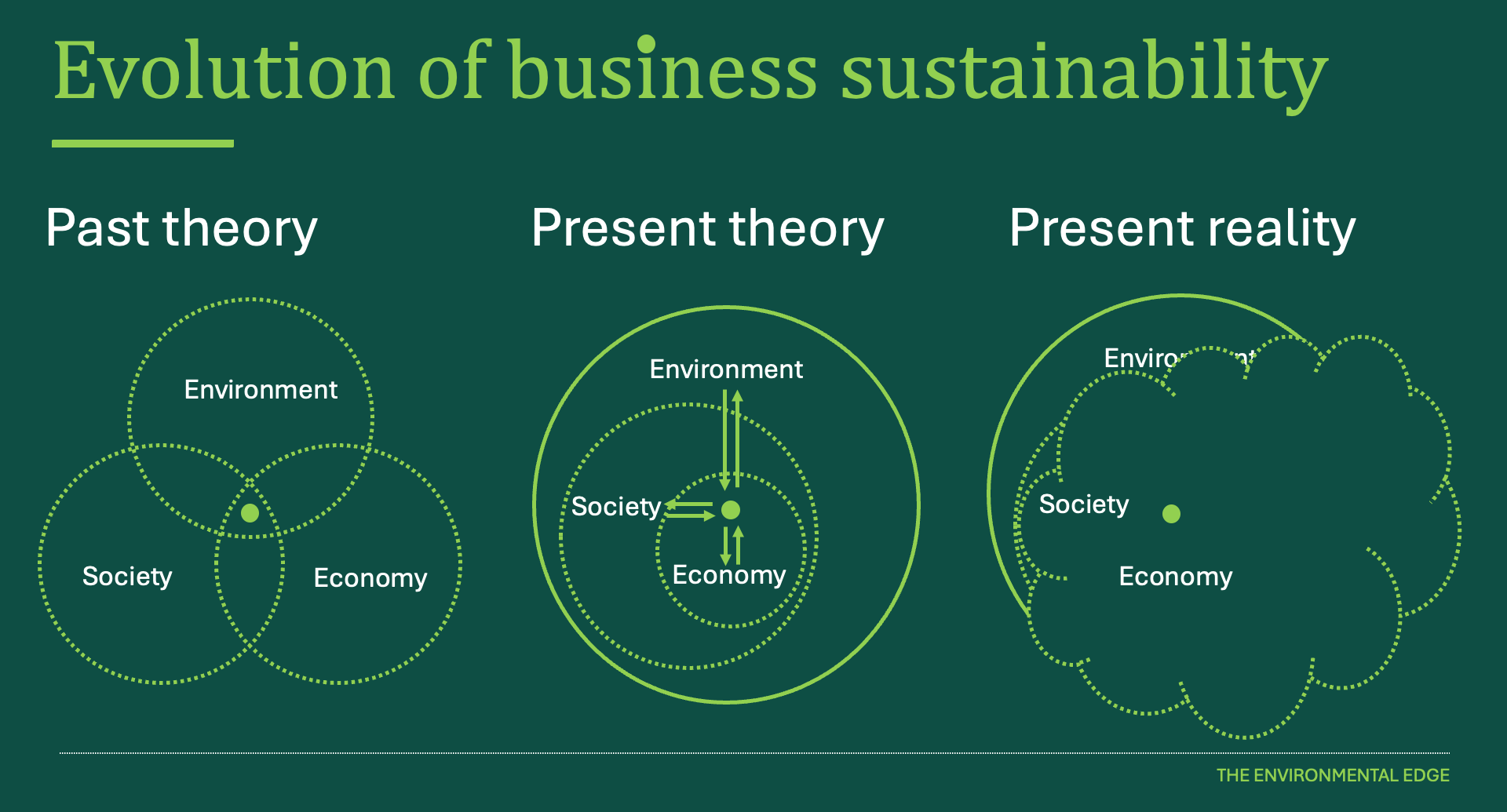

The familiar model with overlapping circles of Economy, Society and Environment – the Triple Bottom Line (aka People, Planet, Profit) articulated by John Elkington in the 1990’s. It envisaged organisations operating at the intersection of these three domains. He subsequently issued a ‘product recall’ (his words) in 2018 as he felt it was not achieving its purpose.

A more recent version places these spheres in a nested hierarchy: the economy sits within society, which sits within the environment. The natural world is a fixed boundary - our ultimate constraint - while societies and economies can expand or contract within it.

Every business impact on and is impacted by all three spheres, as represented by the arrows. Frameworks such as Doughnut Economics model developed by Kate Raworth and Planetary Boundaries by the Stockholm Resilience Centre reinforce this structure with specific social and ecological thresholds.

The last diagram represents current reality: at a global level, the economy and society have exceeded environmental limits. Taken together; social inequality, climate change, ecosystem damage, supply chain fragility and uncontrolled pollution have been referred to as a polycrisis, adding to or, perhaps more accurately, driving global geopolitical uncertainty.

From Doing to Being

Most companies begin by doing sustainability, with an operational and compliance perspective: increasing efficiencies, cutting waste, reducing Scope 1 & 2 emissions, do less harm, comply with regulations, adding sustainability as an agenda item, making the business case for sustainability and producing reports. Sustainability functions and committees are established to demonstrate commitment and manage stakeholder expectations. Sound familiar?

Being sustainable requires a shift in perspective. Executives must consider wider economic, social and environmental impacts, look deeper into their value chain, engage beyond their comfort zone, ruthlessly prioritise a small number of truly strategic issues, integrate relevant tasks into all functions and translate aspirations into execution. It also means asking harder questions: What is the sustainability case for the business? Is the business model sustainable over the long term?

Most organisations exist somewhere between these two states. The following prompts are intentionally challenging, perhaps counter intuitive or even contrarian. They are designed to push leaders further toward becoming truly sustainable in an increasingly uncertain world.

1. Governance

A board’s fiduciary duty—to act in the company’s best interests—implicitly requires understanding environmental and social dynamics that influence long‑term success.

Key questions include:

Does the board have the knowledge and experience to embed sustainability into governance? Are the governance structures appropriate, and if not, how should they evolve (training, expert NEDs, advisory boards, new committees)? Andreas Rasche from the Copenhagen Business School sets out some useful options here.

Are directors asking the right questions and challenging assumptions? Are they receiving the insights that lead to foresight. Safe operating thresholds for seven of the nine planetary processes have now been exceeded[1]. How will the business model be impacted by this reality?

How robustly is the Audit Committee overseeing non-financial data and applying the same rigour used for financial reporting?

Does the Remuneration Committee set meaningful sustainability-linked performance targets for senior executives? (Hint – achieving Scope 1 and 2 GHG emissions reductions is inadequate.)

2. Strategy

Think of your business strategy as your sustainable business strategy. This is less of a leap than it seems. Most strategic processes - horizon scanning, PESTLE analysis, scenario planning - already identify environmental and social issues for the business. Challenge yourself to extend the analysis further and deeper across the value chain.

Do you need a stand-alone ‘sustainability strategy’? While topic‑specific strategies and action plans (e.g. on climate, biodiversity, ethics, health & safety, human rights, DEI) remain essential, a separate sustainability strategy can complicate rather than clarify. If sustainability is truly integrated, a single coherent business strategy may suffice.

3. Risk

Broaden traditional risk management to assess both how your business affects the world (inside‑out) and how the world affects your business (outside‑in).

Start by identifying impacts in both directions (represented by the arrows in the nested model above). For example: how does your value chain activity impact ecosystem services (inside-out) and how dependent is your business on ecosystem services (outside-in)?

Next, reframe risk – the effect of uncertainty on your objectives - as a neutral term with two categories:

Downside risks: threats to be mitigated

Upside risks: opportunities to be captured

This approach can increase engagement by commercial teams in risk management processes, and it completes half of your SWOT analysis.

Begin qualitatively, drawing on internal and external expertise. Detailed processes - stakeholder engagement, data gathering, quantification, scoring, documentation, etc. - can follow once the organisation understands the value of this broader perspective. Open conversations with friends, critics and critical friends are a good place to start.

4. Management

Is a sustainability function necessary? That depends on your organisations size and industry sector. For larger businesses, a small sustainability team can provide expert guidance and support on topics not normally covered by other roles – e.g. climate change and biodiversity – and build capacity and capability in other functions to integrate sustainability into existing management processes. In smaller organisations, this role is usually allocated to an existing function, with external support as required. Operations, EHS, HR and compliance functions are often relatively advanced on related environmental and social expectations, so highlighted below are three functions that may need to consider expanding their remit.

Accounting functions should take ownership of non-financial data and ensure it is managed with the same rigour as financial data: integration into management/board reports and balanced scorecards, inclusion in internal audit and external assurance processes. In addition, accounting professionals should be upskilling on GHG accounting and natural capital accounting where natures stocks and flows of ecosystem services will increasingly be reflected in financial statements (https://www.naturalcapitalireland.com/).

How well are your supply chains understood? Are potential risks uncovered and acted on to reduce fragility and maximise opportunities? Procurement functions have a key role in identify these and acting strategically on the information gathered in relation to human rights, ethics, GHG emissions, pollution, safety, biodiversity, diversity, etc.

As we move from the traditional linear economic model (take-make-dispose) to a more sustainable circular model, product development teams must design for sustainability. Less virgin raw material inputs, increased durability, extended life options and, ultimately, take back for refurbishment or recycling. There are numerous organisations that offer support (https://www.circuleire.ie/, https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/) or even look to the natural world which has been innovating for c. 4 billion years (https://biomimicry.org/).

5. Reporting and Communication

After years of anticipated regulatory reporting requirements, stakeholder questionnaires and multiple voluntary reporting standards and frameworks, reporting fatigue has set in. For many organisations, the reporting tail is wagging the business dog, consuming disproportionate time and resources.

Re-assess your reporting landscape:

Which reports/questionnaires add real business value?

Where are there redundancies, overlaps or immaterial disclosures?

Can you engage with stakeholders to streamline reporting, focusing on what truly matters?

How can you gather reliable sustainability data more efficiently?

For larger companies, can your annual Sustainability Report be merged into your Annual Report to create an Integrated Report?[2] Better still, can more real time data and updates be provided on the website?

Greenwashing undermines integrity and can lead to significant reputational damage to your organisation. Challenge your communications team to only use the word ‘green’ in its chromatic sense – i.e. a colour. If your product or service performs better environmentally or socially, then be precise about the performance criteria and provide independent verification or certification. This may not be straightforward but ultimately can enhance reputation and trust. Other generic terms such as ‘environmentally friendly’, ‘natural’, ‘biodegradable’, or ‘carbon neutral’ are problematic and face legal scrutiny under the Empowering Consumers for the Green Transition Directive. More details from Department of Enterprise here.

Contextualise reported data. Communications on greenhouse gas emissions are often provided without any context. For example, reporting a reduction in selected Scope 3 emissions without at least indicating total Scope 3 emissions is misleading. Are reductions in emissions from employee commuting, business travel or waste generated activities actually significant in the context of the life cycle emissions associated with purchased goods and services, product use, product disposal, etc? Probably not.

There are many challenges facing directors and business leaders today – geopolitical, social, ethical and environmental. Understanding and acting on your organisations material impacts and dependencies on society and the environment builds resilience and even antifragility, a term coined by Nassim Nicholas Taleb the author of Black Swan to describe things that gain from disorder. Organisations that get ahead of the sustainability curve by creating solutions to the polycrisis and becoming ‘net positive’ in the process are the ones that will be sustainable, and successful, in the long term.

About the author

John Barcroft

Founder & Sustainability Consultant

The Environmental Edge

In 2019 John founded his sustainability consultancy and advisory business – The Environmental Edge. He works closely with clients to develop pragmatic sustainable business strategies and practical actions aligned to their strategy, business model, stakeholder expectations, risk management, reporting and future ambitions. John supports executive teams to identify the material sustainability issues in their value chains and then focus on strategies to create business value. With a particular climate change expertise, he provides organisations with the tools and capacity to navigate the challenges of climate governance, strategy, risk and greenhouse gas measurement, metrics and targets. With a collaborative and engaging approach, John guides clients through the often confusing sustainability arena, finding the signals within the noise that lead to more a sustainable and successful organisation over the longer term.

-

Prior to setting up his own business, John was Head of Group Sustainability at DCC plc, an Irish FTSE100 company. Over his 20 year career with DCC, he led the development and implementation of corporate programmes to address DCC’s material sustainability issues, focused on climate change and health and safety. In his role, John engaged with boards and management teams across multiple geographies and divisions (including energy, environmental services, technology distribution, healthcare and food) on both strategy development and execution. Responsibilities included the implementation of GHG accounting processes, a Group wide EHS audit programme, compliance with regulatory reporting, regular reporting to the executive management team and the DCC Board, environmental due diligence for acquisitions, development of best practice guidance and standards and the completion of external corporate sustainability reporting in line with, for example, CDP and GRI voluntary reporting frameworks.

John’s primary degree is in Natural Sciences (Trinity College, University of Dublin). He has also completed a Diploma in Business Studies at the Michael Smurfit School of Business and has a Masters in Environmental Management from Yale University. John has successfully combined his scientific knowledge and business experience to support organisations at varying stages on their sustainability journey. He recently received a Diploma in Company Direction from the Institute of Directors.

John is currently a non-executive director of The Nature Trust - a not-for-profit with a vision for the future of Ireland in which nature thrives. It’s mission is to plant native woodlands at scale across the country and manage them on a non-commercial basis for the benefit of the climate, nature, local communities and wider society.